Nowy artykuł w „Nature” Jeana Vanniera i in. donosi o niezwykłym znalezisku parady trylobitów – grupy pradawnych stawonogów – zabitych i skamieniałych, kiedy maszerowały „gęsiego”. Liczą sobie 480 milionów lat, są z wczesnego ordowiku i znaleziono je w Maroku. (Artykuł można zobaczyć klikając na zrzut z ekranu poniżej, pdf jest tutaj, a odnośnik pod spodem.) To dziwaczne uszeregowanie trylobitów sugeruje jakiś rodzaj zbiorowego zachowania – pierwsze takie znalezisko udokumentowane przez paleontologów*. Ale jaki rodzaj zachowania? Autorzy mają dwie hipotezy i omówię je pokrótce.

Najpierw kilka zdjęć tego gatunku, Ampyx priscus, który ma wydrążony “kolec glabelli” z przodu i dwa „librigenalne kolce” idące do tyłu. Biała linia skali wynosi 1 cm, więc te stworzenia, włącznie z przednim kolcem, mierzyły około 6 cm. Kolce mogły umożliwiać trylobitom wzajemne wyczuwanie się, a więc zachowywanie kontaktu, kiedy poruszały się w szeregu, bardzo podobnie do tego, jak to robią langustowate, kiedy przemieszczają się w szeregu po dnie morskim, jak to pokazuję poniżej. (Każda ”komunikacja” musi być czuciowa, bo te trylobity są ślepe.)

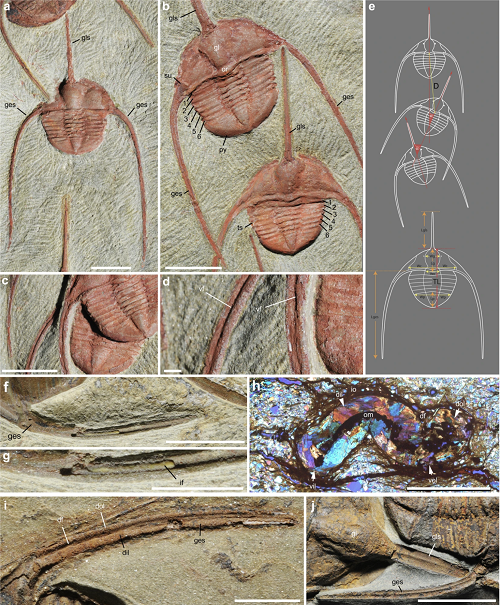

Wszystkie podpisy są wzięte z artykułu w „Nature”. Tutaj są te osobniki ze zbliżeniami ich kolców:

General morphology and parameters of the raphiophorid trilobite Ampyx priscus Thoral, 1935, from the Lower Ordovician (Upper Tremadocian-Floian) Fezouata Shale of Morocco (Zagora area). (a–d) BOM 2481, overall morphology and details of genal spines. (e) Parameters used in measurements. (f,g) MGL 096718, genal spine showing internal mineralized infilling. (h) AA.OBZ2.OI.1, transverse thin section through right genal spine (see general view in Supplementary Fig. 8d). (i) MGL 096727, genal spine. (j) ROMIP 57013, external mould of glabellar and genal spine showing longitudinal ridge. a–d,f,g,i,j are light photographs.

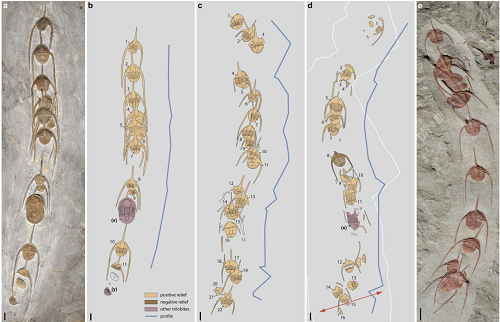

Tutaj są skamieniałości ciągu trylobitów razem z zarysami pokazującymi naturę reliefu kamienia, w jakim zostały zachowane.

Linear clusters of the raphiophorid trilobite Ampyx priscus Thoral, 193531, from the Lower Ordovician (upper Tremadocian-Floian) Fezouata Shale of Morocco (Zagora area). (a,b) AA.TER.OI.12 (see Supplementary Fig. 2a). (c) MGL 096727 (see Supplementary Fig. 5a). (d) AA.TER.OI.13 (see Supplementary Fig. 2b). (e) BOM 2461 (see Supplementary Fig. 2f). (a,e) are light photographs. Line drawings from photographs. Segmented blue lines in (b–d) join the central part of occipital rings of trilobites. Red arrows indicate the position of polished section in Fig. 3. Abbreviations are as follows: (x), Asaphellus aff. jujuanus (asaphid trilobite); (y), juvenile asaphid trilobite. Scale bars: 1 cm.

Tutaj jest wideo langust migrujących w szeregu, bardzo podobnie do tych trylobitów:

Dlaczego więc te pradawne stawonogi maszerowały „gęsiego”? Autorzy odrzucają dwie hipotezy. Pierwsza, że zostały „mechanicznie zgromadzone wzdłuż liniowego, podmorskiego reliefu”. Według tej hipotezy trylobity zniosło w rowki na dnie oceanu i nazbierały się tam, co wyjaśnia długie szeregi. To jednak nie wyjaśnia konsekwentnego uszeregowania zamiast tego, by część została zniesiona prądem tyłem do przodu. Autorzy odrzucają tę hipotezę, ponieważ nie ma żadnej wskazówki z warstw skamieniałości, że były tam te reliefy.

Odrzucają także hipotezę, że te trylobity były uszeregowane w podwodnych norkach a potem uwięzione tam i zabite przez osady. Opierają to odrzucenie na nieobecności „jakichkolwiek zabarwionych zarysów lub zakłóceń w osadach otaczających trylobity”. Zaufam tu autorom, bo wiedza o tym, jak odkryć pradawne norki, jest poza moimi kompetencjami.

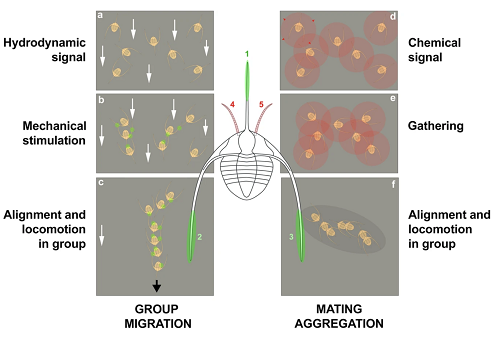

Autorzy oferują dwie inne hipotezy, żeby wyjaśnić to uszeregowanie. Pierwszą, pokazaną po lewej stronie poniżej, jest, że były podwodne sztormy lub prądy, które skierowały trylobity w jednym kierunku, a potem „znalazły” się wzajemnie przez sygnały czuciowe (lub może także chemiczne) tworząc szereg, który spełniał funkcję obronną. Jak mówią autorzy: „Takie mechaniczne kontakty [jak u langust powyżej] wydają się zasadnicze dla spójności grupy i optymalnej koordynacji poruszania się. Maszerowanie ‘gęsiego’ zmniejsza prawdopodobieństwo wykrycia i ataku drapieżnika tworząc dezorientujący obraz w ich [drapieżników] wizualnej percepcji”.

Drugą hipotezą, pokazaną poniżej po prawej stronie, jest to, że trylobity wydzielały chemiczne sygnały, takie jak feromony, jako sposób wzajemnego wykrywania i schodzenia się na płciowe rozmnażanie, z szeregami przypuszczalnie wskazującymi na migracje ku miejscu tarła. Jak piszą autorzy, oba wyjaśnienia mogły działać razem.

Two non-exclusive hypotheses to explain the linear clusters of Ampyx priscus from the Lower Ordovician of Morocco. (a–c) Response to oriented environmental stress (e.g. storms); hydrodynamic signal (higher current velocity represented by white arrows) received by motion sensors triggers re-orientation of individuals; mechanical stimulation and/or possible chemical signals cause gathering, alignment and locomotion in group. (d–f) Seasonal reproductive behaviour; chemical signals (e.g. pheromones; see red circles and red arrows) cause attraction and gathering of sexually receptive individuals (males and females) and migration to spawning grounds. The alignment of individual may have been controlled by mechanical stimuli (as in a–c). Olfactive and mechanical sensors were probably located on the antennules (pink areas 4, 5), and genal and glabellar spines (green areas 1–3), respectively. The exact location of mechanoreceptors is uncertain (possibly on high-relief exoskeletal features such as the glabella).

Jeśli zaś chodzi o to, w jaki sposób zostały pogrzebane razem, to jest to trochę tajemnica, ponieważ trylobity, kiedy są w stresie, podobno zwijają się w kłębek, tak jak nowoczesne równonogi, a te tego nie zrobiły, co widać powyżej. Tutaj jest jeden scenariusz, który wyjaśnia kolejne warstwy, w jakich pogrzebane są szeregi trylobitów.

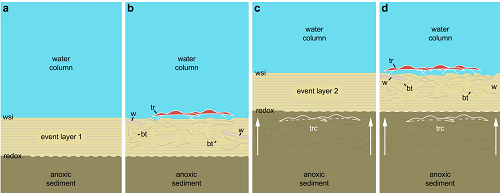

Najpierw, poddane okresowym sztormom, które zakłócały wody, trylobity połączyły się w Wielki Marsz. (Albo, jak napisałem wyżej, mogły maszerować w miejsce rozmnażania się!) Potem sztorm szybko złożył osad na maszerujących trylobitach, fosylizując je in situ. Mogły być dwa inne wydarzenia, które szybko je zakonserwowały: „zatrucie wody”, takie jak uwolnienie siarkowodoru lub, co bardziej prawdopodobne, podnoszenie się ubogich w tlen (“anoksycznych”) osadów, które szybko zabiły trylobity z braku tlenu, a równocześnie ochroniły zwłoki przed padlinożercami.

Można zobaczyć jeden przykład zakonserwowania w panelach a-c poniżej, a potem inną linię formacji trylobitów w panelu „d”:

Scenario to explain the in situ preservation of the Ampyx linear clusters from the Lower Ordovician (Upper Tremadocian-Floian) of Morocco. (a) Deposition of a distal tempestite (event layer 1). (b) Epibenthic (e.g. trilobites) and shallow endobenthic (e.g. possible worms) organisms settle and generate bioturbation above red-ox boundary. (c) Second storm event layer entombs epibenthic fauna in situ; red-ox boundary moves upwards (white arrows). (d) New faunal recolonization. According to Vaucher et al.34, distal storm deposits are relatively thin (less than 5 cm) and consist of a waning (base) and waxing (top) phases (subdivision not represented in this diagram), and depositional environment is that of the distal lower shoreface with a possible water depth of approximately 30–70 m. Bioturbation is based on polished and thin sections (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs 8 and 9). Abbreviations are as follows: bt, bioturbation; tr, trilobite group (Ampyx); trc, trilobite carcasses (Ampyx); w, worm; wsi, water-sediment interface.

Wiele z tego jest zgadywaniem, co jest zrozumiałe przy ograniczonej informacji o tym, co zdarzyło się 500 milionów lat temu. Z pewnością jednak wygląda na to, że – podobnie jak langusty – te trylobity maszerowały w szeregu, prawdopodobnie idąc jeden za drugim przy użyciu czuciowych wskazówek. I w ten sposób mamy rzadki wgląd w zachowanie bezkręgowców z odległej przeszłości.

*Nie jest to pierwsze znalezisko. Analogicznie uszeregowane trylobity znalazł w Górach Świętokrzyskich w 2010 roku Adrian Kin wraz z profesorem Andrzejem Radwańskim i profesorką Urszulą Radwańską. Patrz: https://www.tvp.info/1585856/po-gorach-swietokrzyskich-chodzily-trylobity Przyp. tłum.

______________

Vannier, J., M. Vidal, R. Marchant, K. El Hariri, K. Kouraiss, B. Pittet, A. El Albani, A. Mazurier, and E. Martin. 2019. Collective behaviour in 480-million-year-old trilobite arthropods from Morocco. Scientific Reports 9:14941.

Fossilized trilobites preserved parading in line. But why did they do this?

Why Evolution Is True, 18 października 2019

Tłumaczenie: Małgorzata Koraszewska

Eee, wyglada to na procesje. Wniosek: trollobity byly religijne 🙂